Projection Systems

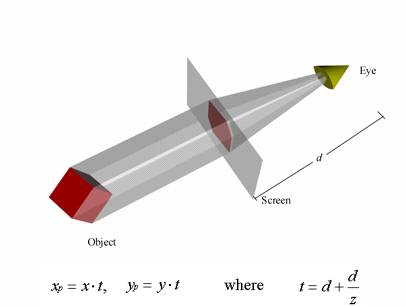

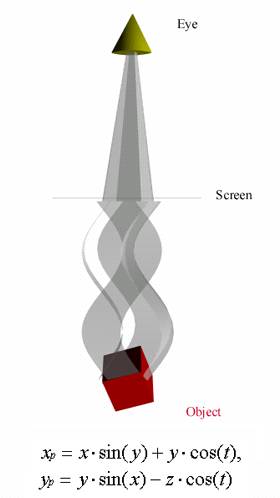

As we have seen earlier, a human viewer observes 3-dimensional solids by projecting their constituent parts (points and faces) on the viewing plane. Perspective systems are designed to construct pictures that, when viewed, produce in the trained viewer the experience of depicted objects that match perceivable objects. It seems that our abilities to see are constrained by the perspective system that we use, that is, by our way of depicting what we see. The kind of pictorial spaces we perceive are expressed through geometrical models. Each model is expressed as a geometrical transformation applied to Euclidean/Cartesian shapes of the physical environment. These transformations show how shapes are projected in pictorial space (see figure below):

The work of Gauss, Riemann, von Helmholtz, and Clifford [3] showed that geometries could be based on axioms other than Euclidean. This means that Euclidean geometry is just one kind of geometry that humans constructed because it made sense for our system of perception. Alternatively, spaces can be constructed on the basis of non-Euclidean geometries revealing behaviors closer to our sensations rather than our perception. For example, the idea of hyperbolic space, or insect space, or cubistic space may come to mind.

In Euclidean geometry, if the viewing plane is placed at the origin along the z-axis, then any point (x,y,z) in viewing coordinates is transformed to projection coordinates (xp,yp) as:

![]()

In parallel projection the z-coordinate value is omitted. In contrast, in perspective projection, the z-coordinate value is involved in the transformation equations of the projection. If the viewing plane is placed along the z axis, then any point (x,y,z) in viewing coordinates is transformed to projection coordinates as:

![]()

and d is the distance of the viewer to the viewing plane.

These two projections systems were implemented earlier in the following code:

//*************

public MyPoint

setAxonometric(){

MyPoint p = new

MyPoint(0., 0., 0.);

p.x = x;

p.y = y;

return p;

}

//*************

public MyPoint

setPerspective(){

MyPoint p = new

MyPoint(0., 0., 0.);

double d =

1.0/(1.0-((double)z/512.)); //Perspective projection

p.x = x * d;

p.y = y * d;

return p;

}

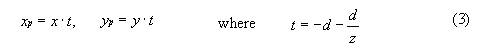

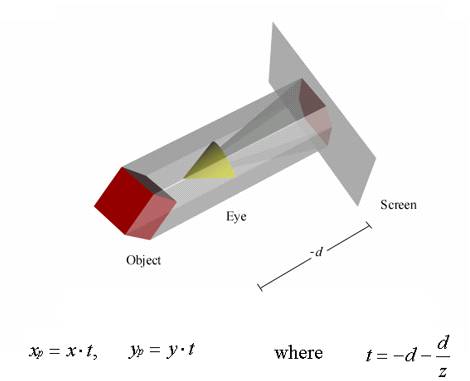

What if, in the above code, we give d a negative value? What would that look like? What would it mean? It may be hard to imagine so lets implement it and see. If d is negative the viewer is assumed to be in the opposite position of the viewing plane and the perspective projection equations become:

From the viewer's point of view, the effect of this alteration was an inverted world where faces of objects appear to be inside out and movements appear to shift surprisingly in the opposite direction. The implementation of this in Java is:

//*************

public MyPoint

setRevPerspective(){

MyPoint p =

new MyPoint(0., 0., 0.);

double t =

1.0/(1.0-((double)z/-512.));

p.x = x * t;

p.y = y * t;

return p;

}

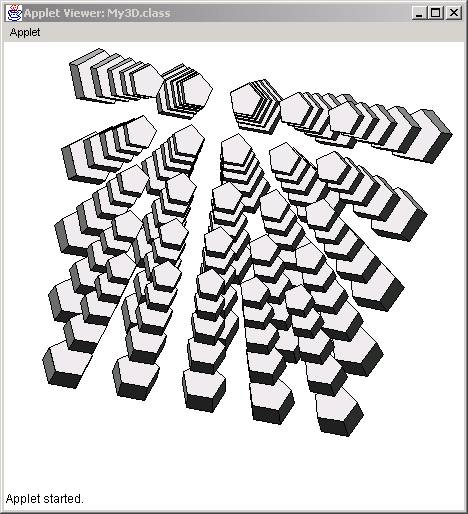

The result is:

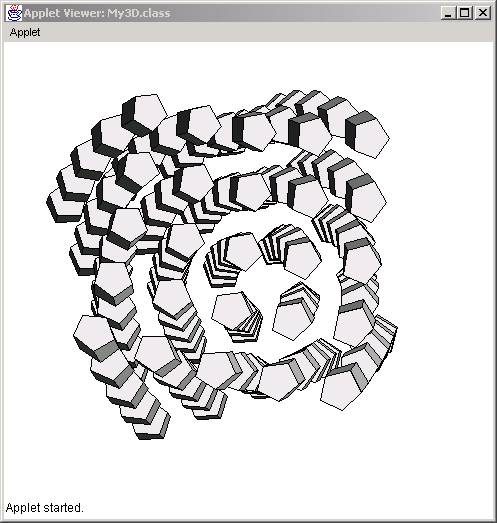

Along the same line of thought, projection of a point (x,y,z) on a viewing plane does not have to occur along a single straight or curved line as the previous experiments did. In fact, many creatures view the world by collecting information from different points of view at the same time and their eyes are not always spherical. Thus, lets rotate the viewing projection lines to become trigonometric curves the projection equations can become as follows:

![]()

The code implementation of such a projection would be:

//*************

public MyPoint

setCylPerspective(){

MyPoint p = new

MyPoint(0., 0., 0.);

double d = 1.0/(1.0-((double)z/-512.));

d = 512./( 512.-

z); //Perspective projection

p.x

= (int)((x*Math.sin(d) + y*Math.cos(d)));

p.y

= (int)((y*Math.sin(d) - x*Math.cos(d)));

return p;

}

The result is:

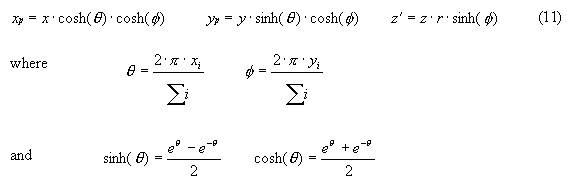

In hyperbolic space -- one of the non-Euclidean geometries -- the formulas involve the hyperbolic sine and cosine functions (sinh and cosh), that are exponential. Hyperbolic space is infinite in extent, just like Euclidean space. However, it is possible to map the entire infinite space into a finite portion of Euclidean space. It might surprise you that you can map an infinite amount of space with "more room" into a finite piece of a space with "less room", but non-Euclidean geometries have many unexpected consequences for Euclidean intuitions. The equations used are:

The implementation code can be seen below:

//*************

public MyPoint

setHyperbolicProjection(){

MyPoint p = new MyPoint(0., 0., 0.);

double anglex = x*0.017453;

double angley = y*0.017453;

double sinhx = (Math.pow(Math.E, anglex) - Math.pow(Math.E, -anglex))/

(Math.pow(Math.E, anglex) + Math.pow(Math.E, -anglex));

double sinhy = (Math.pow(Math.E,

angley) - Math.pow(Math.E, -angley))/

(Math.pow(Math.E,

angley) + Math.pow(Math.E, -angley));

p.x = (int)(400 * sinhx * 0.5 );

p.y = (int)(400 * sinhy * 0.5);

return p;

}

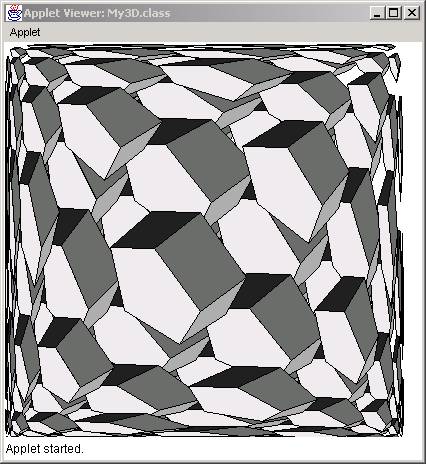

The result of this mapping is shown below: