- Defining a new class called MyPoint

So far we have dealt with one-file classes, that is, classes that reside on one single file with the same name. But if later we start adding more and more methods in the file, the file may become huge and inefficient to search, run, or organize. We break therefore the methods into files and inside each file we write the code for organized sets of variables and methods called classes. In that way we break the program in files each of which contains information blocks.

First, we will create a new file called MyPoint.java and inside that file, we will define a new class called MyPoint. This new class will be used to store information about points and their related methods (such move, rotate, scale, etc). Here is the new class:

public class MyPoint {

int x, y; //members

public MyPoint(int xin, int yin){ //constructor

x = xin;

y = yin;

}

}

The class is called MyPoint and is public (so it can be used by other classes). It is composed of two sections: the members and the constructor.

- In the members area we put all the variables that are associated with the class. In this case, since it is a point we are talking about the members of a point should logically be its coordinates, which we will call x and y.

- The second section is the constructor. In that area we assign values to the members. So in this case, to construct MyPoint we need to pass two variables xin and yin (or two numbers) that are then assigned to the members x and y.

This new class we save as MyPoint.java and we add it to the project.

![]()

To use the newly defined class we need to call it from the main area of simple.java. Here is how we call it:

import java.applet.*;

public class simple extends Applet{

//*****************************************

public void init(){

MyPoint p = new MyPoint(100, 200);

System.out.println(" x = " + p.x + " y =

" + p.y);

}

}

The statement

MyPoint p = new MyPoint(100, 200);

says that we are a) declaring a new object p of type MyPoint and b) allocating memory (that is the “new” word) to create a new MyPoint to which we pass 100 and 200 as the x and y coordinates. After this the program goes to the MyPoint.java file and looks for the constructor. When it sees the constructor:

public MyPoint(int xin, int yin){ //constructor

x = xin;

y = yin;

}

xin is 100 and yin is 200 and therefore x member is 100 and y member is 200. Now when we want to printout the members of MyPoint, we use the statement:

System.out.println(" x = " + p.x + " y = " + p.y);

We get access to x and y of object p by using the “.” operator that simply says “go to object p and give me the member x”, that is, p.x (same for y).

17.1

Adding methods to a class

Now the reason why we created a MyPoint object was to facilitate operations on points by organizing and concentrating them in the class’s area. Suppose that we want to introduce randomness in the MyPoint class. We then need to assign random coordinates to the members x and y. Therefore we need to create a method, (which we will call randomize) and this will do the job of randomness (given a range).

public class MyPoint {

int x, y; // members of

class

//********** Constructor

public MyPoint(int xin, int yin){

x = xin;

y = yin;

}

//********** Method

public void randomize(int range){

x = (int)(range * Math.random());

y = (int)(range * Math.random());

}

}

The method randomize (which is public) takes one argument, the integer range. Then it creates two random numbers which it assigns to members x and y of the MyPoint class. This method is invoked (or called) from the main code through the following statements:

import java.applet.*;

public class simple

extends Applet{

//*****************************************

public void init(){

MyPoint p = new MyPoint(100, 200);

System.out.println(" x = " + p.x + " y =

" + p.y);

p.randomize(10);

System.out.println(" x = " + p.x + " y =

" + p.y);

}

}

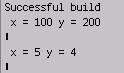

With the statement p.randomize we call the method randomize that assigns new values to x and y within the MyPoint class. So x and y are now different. We then printout x and y and the output result is:

The first printout was the predictable 100 and 200 that we assigned and the second printout was two random numbers between 0 and 10, which are 5 and 4.

Notice that in the MyPoint class the method randomize takes as a return value “void”, which means that randomize does not return anything directly. Instead, it does its job by changing the values of x and y which are then accessed indirectly through the calls p.x and p.y. Another thing worth mentioning is that the constructor MyPoint does not take “void” because it is not a method. The syntax of a constructor is to simply define it with the same name as the class (and the file) without any identifiers (except public).

17.2. Organization

of classes

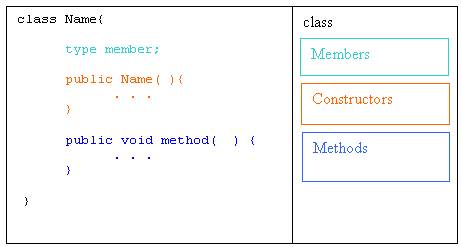

Any class is composed of three parts:

a) its members

b) its constructors

c) its methods.

In the MyPoint class we have the following:

a) members, those were x and y

b) constructors, those were public MyPoint(int xin, int yin){

c) methods, those were public void randomize(int range){

Members and methods can be access by external classes using the “.” symbol as in

p.x or p.y or

p.randomize(10);

The constructors are accessed only once (to create the class) and we use the “new” symbol as in

MyPoint

p = new MyPoint(100, 200);

We can have more than one constructor and we distinguish them from the number of arguments that are being passed. For example:

public

MyPoint(int xin, int yin){

x =

xin;

y =

yin;

}

and

public

MyPoint( ){

x =

0;

y =

0;

}

can both co-exist within the same class MyPoint except that when we call MyPoint( ) it assigns 0;s to x and y as opposed to MyPoint(100, 200) which assigns 100 and 200.

The same applies to methods where we may have to or more methods with the same name that are distinguish them from the number of arguments that are being passed.

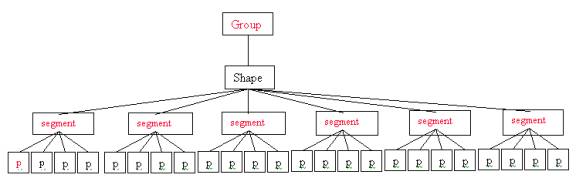

As you may have suspected classes are created in order to organize the code better and to minimize repetitive patterns. The declaration of a class is related to its self-consistency. We usually declare as classes objects that have some kind of a self-consistency and completeness. For example, if we are going to be dealing with 2D shapes it makes sense to declare as classes the following entities: a point, a segment, a shape, and a group. Every time we want to create or modify a group we have to create or modify its constituent parts that is the segments and the points.

In the following section we will create three classes that will illustrate the compositional tree structure of classes. We will create the following classes: MyPoint, MySegment and MyShape.

17.3. Class MyPoint

This class is similar to the one we created in the previous section except that we will declare x and y to be double numbers because in real life locations can be fractional, i.e. .3.5 meters or 2’ 11”, etc. We will cast them to integers only when we draw to the screen (since pixels are whole numbers).

public class MyPoint {

double x, y; // members

of class

//********** Constructor

public MyPoint(double xin, double yin){

x = xin;

y = yin;

}

//********** Method1

public void randomize(int range){

x = range * Math.random();

y = range * Math.random();

}

//********** Method2

public void move(double xoff, double yoff){

x = x + xoff;

y = y + yoff;

}

}

17.4. Class MySegment

The next class is MySegment

which represents a segment. Therefore

its members should be two points (a start and an end). We construct a segment by passing two

MyPoints p1 and p2 that are assigned to its members start and end. T o move a segment all we need to do is to

call the move method of its members, which happen to be of MyPoint type (we are

using start.move and end.move which call the move method in the MyPoint

class). Finally to draw we need to pass

the graphics g because we are using g.drawLine. The parameters are the x and y members of start and end, which we

cast to integers in order to draw at pixel locations on the screen (that is

what the method g.drawLine(int x1, int y1, int x2, int y2) accepts anyway)

import java.awt.*;

public class MySegment {

MyPoint start; //

members of class

MyPoint end;

//********** Constructor

public MySegment(MyPoint p1, MyPoint p2){

start = p1;

end = p2;

}

//********** Move

public void move(double xoff, double yoff){

start.move(xoff, yoff);

end.move(xoff, yoff);

}

//*********** draw

public void draw(Graphics g){

g.drawLine((int)start.x, (int)start.y, (int)end.x,

(int)end.y);

}

}

17.5.Class

MyShape

This class takes as

input segment but the problem is that (unlike MySegment) we do not know

in advance how many segment are needed to construct a shape. Could be 3 (for a triangle), could be 24

(for a 24-gon), or could be anything.

So we use an array of segments (MySegment[]) which we

call

segs. The constructor MyShape

take two input variables: the number of segments and the array of

segments. These two variables are

assigned to the class members numSegments and segs. To assign the input array to the member

array we loop through the arrays assigning the input value one at a time.

for(int i=0;

i<numSegments; i++)

segs[i] = inputSegments[i];

The move and draw methods are pretty straightforward. All we do is to invoke the segment methods move and draw of the member segs[i] one at a time.

import java.awt.*;

public class MyShape {

MySegment[] segs; //

members of class

int numSegments;

//********** Constructor

public MyShape(int numInputSegments, MySegment[]

inputSegments){

numSegments = numInputSegments;

segs = new MySegment[numSegments];

for(int i=0; i<numSegments; i++)

segs[i] = inputSegments[i];

}

//********** Move

public void move(double xoff, double yoff){

for(int i=0; i<numSegments; i++)

segs[i].move(xoff, yoff);

}

//*********** draw

public void draw(Graphics g){

for(int i=0; i<numSegments; i++)

segs[i].draw(g);

}

}

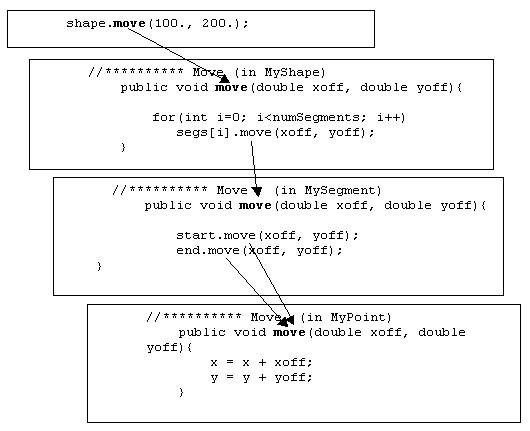

The structure of these classes works as follows: when a method is called at the top, thata method calls its corresponding method of the calss right below all the way to the bottom classes that do the job. For example, a call to shape.move(x, y) will call the (in a loop) the MySegment’s method “move”, which in turn will call the MyPoint’s method “move” which will do the actual movement.

For example, suppose that the main class (simple) looks as follows:

import java.applet.*;

import java.awt.*;

public class simple

extends Applet{

MyPoint p1, p2, p3, p4;

MySegment[] segment = new MySegment[2];

MyShape shape;

//*****************************************

public void init(){

p1 = new MyPoint(100., 100.);

p2 = new MyPoint(200., 200.);

p3 = new MyPoint(200., 200.);

p4 = new

MyPoint(300., 100.);

segment [0] = new MySegment(p1, p2);

segment [1] = new MySegment(p3, p4);

shape = new MyShape(2, segment);

}

//*****************************************

public void paint(Graphics g){

shape.move(100., 200.);

shape.draw(g);

}

}

We first declare points p1, p2, p3, p4, two segments segment (actually one array with two positions) and a shape called shape. In the init() method we create all the objects: first we create four points (with hard coded values), then we fill the two array positions creating two segments and finally we create a shape that need the number of segments (that is 2) and the array containing the segments. Once these are accomplished we call the paint method. In the paint method all we do is make two references to move and draw of class shape. Here is what is happening:

shape.move(100., 200.);

in class simple calls the move method of MyShape. That invokes the method

public void move(double

xoff, double yoff){

which in turn loops and invokes the move method of the MySegment class

for(int i=0; i<numSegments; i++)

segs[i].move(xoff, yoff);

which in turn invokes twice the move method of the MyPoint class

public void move(double

xoff, double yoff){

start.move(xoff, yoff);

end.move(xoff, yoff);

}

which in turn assigns the moved offsets to the x and y members of the MyPoint class:

public void move(double

xoff, double yoff){

x = x + xoff;

y = y + yoff;

}